The Kid

Directed by Charlie Chaplin

TW: Parental abandonment

Comedy is a hard thing to do. Over time I've become more and more reserved in my comedic senses and don't typically enjoy the genre. My favorite comedy movie is probably The Big Lebowski, which I enjoy primarily due to the very well-written dialogue-based comedy which builds over the course of the film. As far as other comedy goes, I enjoy It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Community and Tim and Eric but beyond these I tend to find a lot of comedy pretty hackneyed and reliant on a shared sense of humor. If the sense of humor isn't shared between writer and audience, the comedy can fall flat.

It's nice, then, that The Kid has held up so well over time. It's actually a pretty impressive movie in its own right, with lots of wonderful choreography and impressive shots, but I want to highlight that the movie is one of the few I've found funny in years. Chaplin and Coogan play well off of one another and so many of the scenes are brilliantly choreographed. In my opinion, slapstick is like a dance, and to do slapstick well requires a lot of precision in making things look like accidents.

The plot of the movie is okay for what it is. An unnamed woman gives birth to a child, and due to complications with the father, decides to abandon the child in the back seat of an expensive car, leaving a note asking whoever finds the child to take care of it. The car is stolen and the thieves, upon discovering the child, leave him on the street where he is found by Chaplin's 'tramp'. The tramp takes the child in and becomes a father to the child, who eventually becomes a player in the tramp's con-artist game.

The woman, now distraught over her child and wealthy, takes to charity work among the poor, where she comes across her child (now named 'John'), but the two do not recognize one another. When John becomes sick one day, the woman offers to call a doctor. The doctor, upon finding out that the child is not the tramp's biological son, calls an "orphan asylum" to take the child away. Hijinks ensue and the tramp and John are left wandering the streets, avoiding the authorities. Eventually, the child is given over to the police (kidnapped, actually) and the woman arrives to take him back.

The Tramp, now tired after having searched for John all night following his kidnapping, falls asleep on his doorstep and has a pretty bizarre dream sequence where various characters in the movie are now angels. The Tramp becomes an angel too and all seems good until three devils sneak into the gated neighborhood where the angels are living. Things go downhill from here until The Tramp is shot and wakes up to find that he's being hoisted up by a police officer. The officer takes him to see the woman and the child, who welcome him inside the woman's mansion gladly.

So I don't really want to talk about the plot to this one. I have some pretty conflicted feelings about how the child's custody is handled throughout the film. Maybe I'm being too harsh here, but it seems to me that the woman is thoroughly in the wrong for having abandoned her child. Not necessarily for the decision to not take care of a child herself (plenty of circumstances arise that make child raising by a particular parent a bad decision for all parties) but in her method of trying to find an adoptive parent by literally leaving the child in the backseat of a car with a note. I understand she was trying to put the child to a well-off family, but it's still reckless endangerment.

But like I said, I'm more interested in talking about the comedy; or the dramedy more accurately. I'm amazed at how much this film conveys through visuals alone. One of the things I think people oftentimes forget about silent films is that not all dialogue needs to be given an intertitle. So much of the dialogue can be inferred or left to the imagination of the viewer and, far from something being lost, I think a lot is added to a film as a result.

I'm actually really pleased that I found this film. I remember watching Modern Times back in undergraduate, and I thought it was okay. Now, having seen this, I'm really looking forward to checking out the Harold Lloyd and Chaplin films that are also on my list.

Monday, December 19, 2016

Sunday, December 18, 2016

The Phantom Carriage (Körkarlen)

The Phantom Carriage

Directed by Victor Sjöström

TW: Talk of abuse, alcoholism, suicide, illness, death

You're a complicated man, David Holm.

It's New Years Eve, and two people lay dying, one will become this year's carriage driver, the other will be taken away.

This is the interesting mythology set up in the beginning of The Phantom Carriage. The last person to die before midnight of the new year must become the driver of the titular phantom carriage, performing a grim reaper role for the following year until a new person takes their role at the end. While time zones obviously present a complication to this, we're very much working in the world of folklore on this one, and while the film begins with some interesting shots of the carriage driving around the countryside, picking up accident victims, the carriage is actually fairly incidental to the plot.

The plot instead revolves around the two dying people. One of them, Sister Edit, is concerned for the welfare of the other, a man by the name of David Holm. After sending a colleague and friend to go asking around for him, she goes back to resting in anticipation of her death.

David Holm, for his part, is not exactly a well-off sort. Sister Edit's colleague finds Holm drunk with two friends in a cemetery. After telling Holm the situation, he refuses to come see Edit. Afterward, Holm's two fellow homeless friends begin to berate him for his choice. A fight breaks out and Holm is killed in the struggle.

Now here's where the movie kind of changes gears, and where its classification as a horror movie (on wikipedia and other websites) comes into question a bit. When Holm dies, he's approached by the driver of the phantom carriage, Georges (a former companion of David's), who tells him the situation. Holm is the last one to have died in the year and so he'll be the new driver of the carriage. Holm is then guided through a reflection by Georges as he's asked to remember how his life has come to this point.

We're then given an extended flashback which makes up the bulk of the film. David Holm was once a family man with a wife and two children who he seemed to love very deeply. Between edits, we're informed that he was led astray to alcoholism by Georges. After falling unconscious in front of his house one evening, David Holm awakens in jail. The policeman here is really pretty ridiculous in terms of his talking to Holm. He informs David that his brother has committed murder and that somehow this is David's fault for the two of them drinking the night before.

Now if this is where the film stayed, I could see David Holm as a sympathetic figure; in a sort of "one bad choice" kind of way. However, this is based on the previous characterization of Holm as a pretty alright guy only recently convinced to start drinking by Georges. Instead, when David is let out of jail he returns to his apartment to find it empty, his wife, Anna, having left with the children to get away from him. So, what does he do?

He vows vengeance against them. It's such a drastic change in tone and it's like David Holm just dedicates himself to being the most awful person he can from there on out. He is driven into poverty over his country-wide search for Anna and one New Year's Eve, he arrives at a Salvation Army shelter that's just been opened by Sister Edit. Sister Edit is such a bundle of goodness, just happy to do her job for a person in need of help. She gladly lets David stay the night, taking his coat to mend overnight as he rests.

The next morning, David is awoken by another worker in the shelter and is given a breakfast and his newly mended coat. Impressed by the mending, he asks to meet Sister Edit. Upon her arrival, smiling and all anticipation, he rips the jacket apart in front of her, undoing all of her work just to be a jackass. Sister Edit, cinnamon roll that she is, asks him to please return in one year's time on the next New Year's Eve, as she had prayed that their first visitor would find good fortune over the next year. He agrees, seeming to relish the thought of breaking her faith.

Real pleasant guy.

Georges then tells David that he's going to make him fulfill his promise. After working some ghosty-magic, he binds David and takes him to Sister Edit's side. Edit cannot see David, but sees Georges, begging him not to take her before David comes to visit her. David seems to be distraught over her situation, and we're given another flashback.

Over the next year following David's original visit to the shelter, Sister Edit runs into David Holm a few times and despite the fact that she has now contracted tuberculosis from the bacteria on his coat, she is still insistent that he try to better himself. Holm, for his part, grows more and more monstrous as if to spite her. He shows up at a Salvation Army meeting and begins coughing on people, hoping to spread his sickness further.

Just as it happens, Anna is at that Salvation Army event, and approaches Sister Edit about David afterward. Edit is insistent that the two reconcile and manages to arrange a meeting between the two (would not have advised that at this point).

David and Anna reunite and David is surprisingly not a total dick about the situation. The two seem to reconcile and decide to give it another shot. However, we see that a few weeks later David's reverted to his old ways and is now even NOT CONCERNED ABOUT INFECTING HIS CHILDREN WITH TUBERCULOSIS. When Anna asks that he not, he coughs on them directly. Anna manages to lock him in the kitchen of their house as she tries to take the children and leave. David, realizing that he's locked in, reveals the fact that he was an inspiration for Stanley Kubrick's version of Jack Torrance and begins axing the door to pieces. Anna faints before she can get away with the children and David escapes and tries to get his wife awake.

We come back to Edit, who BLAMES HERSELF FOR DAVID'S DEEDS BECAUSE SHE BROUGHT THE COUPLE BACK TOGETHER. David manages to get Edit to see him, showing that he is moved by her admission of guilt and she dies in peace. Georges tells David that she won't be coming with, she'll have a different emissary coming for her, and he and David leave as they have one more errand that night before David is to take over the job.

They arrive at David's house, where he finds that his wife, afraid for their children's welfare due to the fact that she is also dying of consumption, is planning to poison both the children and herself. David, horrified by this, asks Georges to intervene, but Georges tells him that he has no control over the living. After pleading, David suddenly regains consciousness in the cemetery, running home to stop Anna from committing suicide. He arrives and manages to stop her, the two embrace as David mutters a prayer, promising to reform.

This film is complicated for me. On the one hand it is a beautiful film - wonderfully edited, orchestrated, and shot. The concept of the carriage itself is an interesting one, and Sister Edit is a bundle of goodness. But goddamn David Holm is just not a sympathetic character. He may've been at one point, but his actions across the course of the film paint him as a repulsive man who maliciously attempted to make everyone else's life as miserable as he could. I mean, I'm all for film's featuring bleak characters, but I'm a bit more conflicted about this film's presentation of Holm as a tragic character with hope for redemption at the end. While maybe he can reform, his actions seem to paint the picture of a really horrible person over the course of the film, and maybe the film is a bit more like Sister Edit in terms of its certainty that he can reform, but I'm a bit skeptical.

Directed by Victor Sjöström

TW: Talk of abuse, alcoholism, suicide, illness, death

You're a complicated man, David Holm.

It's New Years Eve, and two people lay dying, one will become this year's carriage driver, the other will be taken away.

This is the interesting mythology set up in the beginning of The Phantom Carriage. The last person to die before midnight of the new year must become the driver of the titular phantom carriage, performing a grim reaper role for the following year until a new person takes their role at the end. While time zones obviously present a complication to this, we're very much working in the world of folklore on this one, and while the film begins with some interesting shots of the carriage driving around the countryside, picking up accident victims, the carriage is actually fairly incidental to the plot.

The plot instead revolves around the two dying people. One of them, Sister Edit, is concerned for the welfare of the other, a man by the name of David Holm. After sending a colleague and friend to go asking around for him, she goes back to resting in anticipation of her death.

David Holm, for his part, is not exactly a well-off sort. Sister Edit's colleague finds Holm drunk with two friends in a cemetery. After telling Holm the situation, he refuses to come see Edit. Afterward, Holm's two fellow homeless friends begin to berate him for his choice. A fight breaks out and Holm is killed in the struggle.

Now here's where the movie kind of changes gears, and where its classification as a horror movie (on wikipedia and other websites) comes into question a bit. When Holm dies, he's approached by the driver of the phantom carriage, Georges (a former companion of David's), who tells him the situation. Holm is the last one to have died in the year and so he'll be the new driver of the carriage. Holm is then guided through a reflection by Georges as he's asked to remember how his life has come to this point.

We're then given an extended flashback which makes up the bulk of the film. David Holm was once a family man with a wife and two children who he seemed to love very deeply. Between edits, we're informed that he was led astray to alcoholism by Georges. After falling unconscious in front of his house one evening, David Holm awakens in jail. The policeman here is really pretty ridiculous in terms of his talking to Holm. He informs David that his brother has committed murder and that somehow this is David's fault for the two of them drinking the night before.

Now if this is where the film stayed, I could see David Holm as a sympathetic figure; in a sort of "one bad choice" kind of way. However, this is based on the previous characterization of Holm as a pretty alright guy only recently convinced to start drinking by Georges. Instead, when David is let out of jail he returns to his apartment to find it empty, his wife, Anna, having left with the children to get away from him. So, what does he do?

He vows vengeance against them. It's such a drastic change in tone and it's like David Holm just dedicates himself to being the most awful person he can from there on out. He is driven into poverty over his country-wide search for Anna and one New Year's Eve, he arrives at a Salvation Army shelter that's just been opened by Sister Edit. Sister Edit is such a bundle of goodness, just happy to do her job for a person in need of help. She gladly lets David stay the night, taking his coat to mend overnight as he rests.

The next morning, David is awoken by another worker in the shelter and is given a breakfast and his newly mended coat. Impressed by the mending, he asks to meet Sister Edit. Upon her arrival, smiling and all anticipation, he rips the jacket apart in front of her, undoing all of her work just to be a jackass. Sister Edit, cinnamon roll that she is, asks him to please return in one year's time on the next New Year's Eve, as she had prayed that their first visitor would find good fortune over the next year. He agrees, seeming to relish the thought of breaking her faith.

Real pleasant guy.

Georges then tells David that he's going to make him fulfill his promise. After working some ghosty-magic, he binds David and takes him to Sister Edit's side. Edit cannot see David, but sees Georges, begging him not to take her before David comes to visit her. David seems to be distraught over her situation, and we're given another flashback.

Over the next year following David's original visit to the shelter, Sister Edit runs into David Holm a few times and despite the fact that she has now contracted tuberculosis from the bacteria on his coat, she is still insistent that he try to better himself. Holm, for his part, grows more and more monstrous as if to spite her. He shows up at a Salvation Army meeting and begins coughing on people, hoping to spread his sickness further.

Just as it happens, Anna is at that Salvation Army event, and approaches Sister Edit about David afterward. Edit is insistent that the two reconcile and manages to arrange a meeting between the two (would not have advised that at this point).

David and Anna reunite and David is surprisingly not a total dick about the situation. The two seem to reconcile and decide to give it another shot. However, we see that a few weeks later David's reverted to his old ways and is now even NOT CONCERNED ABOUT INFECTING HIS CHILDREN WITH TUBERCULOSIS. When Anna asks that he not, he coughs on them directly. Anna manages to lock him in the kitchen of their house as she tries to take the children and leave. David, realizing that he's locked in, reveals the fact that he was an inspiration for Stanley Kubrick's version of Jack Torrance and begins axing the door to pieces. Anna faints before she can get away with the children and David escapes and tries to get his wife awake.

We come back to Edit, who BLAMES HERSELF FOR DAVID'S DEEDS BECAUSE SHE BROUGHT THE COUPLE BACK TOGETHER. David manages to get Edit to see him, showing that he is moved by her admission of guilt and she dies in peace. Georges tells David that she won't be coming with, she'll have a different emissary coming for her, and he and David leave as they have one more errand that night before David is to take over the job.

They arrive at David's house, where he finds that his wife, afraid for their children's welfare due to the fact that she is also dying of consumption, is planning to poison both the children and herself. David, horrified by this, asks Georges to intervene, but Georges tells him that he has no control over the living. After pleading, David suddenly regains consciousness in the cemetery, running home to stop Anna from committing suicide. He arrives and manages to stop her, the two embrace as David mutters a prayer, promising to reform.

This film is complicated for me. On the one hand it is a beautiful film - wonderfully edited, orchestrated, and shot. The concept of the carriage itself is an interesting one, and Sister Edit is a bundle of goodness. But goddamn David Holm is just not a sympathetic character. He may've been at one point, but his actions across the course of the film paint him as a repulsive man who maliciously attempted to make everyone else's life as miserable as he could. I mean, I'm all for film's featuring bleak characters, but I'm a bit more conflicted about this film's presentation of Holm as a tragic character with hope for redemption at the end. While maybe he can reform, his actions seem to paint the picture of a really horrible person over the course of the film, and maybe the film is a bit more like Sister Edit in terms of its certainty that he can reform, but I'm a bit skeptical.

Häxan

Häxan

directed by Benjamin Christensen

TW: for discussion of oppression, historical torture (inquisitions mostly), religious abuse, and coerced psychiatry.

How do we take a movie like Häxan? In some ways I feel like watching this is akin to watching DW Griffith's Birth of a Nation. On one hand, it's a piece of filmic history, on the other it's a reiteration of what were (and are) systemic injustices and violences done upon various marginalized bodies (women in the former and black people in the latter).

I'll grant that Häxan is probably not as purposefully inflammatory as Griffith's film. It takes its subject, the history of witchcraft and the treatment of women accused as witches throughout history, as a symptom of a bygone superstitious belief system supplanted by scientific insight and more modern medicine.... but that's.. well we'll get there.

The film begins with a recounting of various myths from throughout history, landing on how the conception of medieval Christianity conceived of the world as existing in spheres, at the top of which sat the Christian God and at the bottom of which was found Hell.

From here, we're informed of the belief that throughout history certain women were perceived as being particularly susceptible to the influence of the devil. It's interesting that the movie's portrayal of this history is very much of a double consciousness about this. On the one hand, these women are to be pitied and helped (oh the help...), but this is most often when they are in the company of men. When these women congregate together, they are feared. There are some really stunning shots during this part of the movie as the film shows the witches in flight across various nighttime foreground structures.

From this somewhat empowering view of the witch as an object of fear, the movie then moves us forward to a period where religious persecution holds sway. In this segment of the movie, we see that the movie does at least know that the treatment of women at this time was vile. Women are pressured into confessions under threat to their loved ones, and are routinely killed after enduring horrible torture at the hands of these monks and inquisitors. It's really at times some pretty brutal stuff, and there's a real sense of the injustice of the time.

After wrapping this up, the film begins its conclusion that's a bit... well, it's cause for reflection. The film was made in 1922, and I imagine was one of the very early documentary style films. The film has a very "look how far we've come" attitude about the attitudes toward women. Saying that what used to be called witchcraft.... is now properly known as hysteria....

The funny thing is, I think the film's a bit of a mirror. So many people still berate feminists with this idea that because women are now able to do X action (vote, work, have birth control), that we've somehow totally overcome sexist ideology. In this way, Häxan seems less like an opportunity to shake our heads at the ignorance and misogyny of these people in 1922, and more as an invitation to look at how this same sort of pattern of thought is ongoing and insidious, and that changes to ideology (such as the introduction of intersectionality to feminism) are needed as a fine-tuning instrument, lest we claim some action or movement as a panacea for oppression (as psychiatry is posited in this film).

Given this, I also think that the sympathetic portrayal of the witch is interesting. I have several female-identifying friends who associate strongly with various forms of witchcraft, paganism, and Wicca. I think that in some ways these are oftentimes counter-narratives that go against the patriarchal narratives instituted by Western Abrahamic religious hegemony. It's a subversive tactic, and the shot that I'm reminded of the most comes from the end of the witch segment of the movie. In it, it's explained that it was believed that witches would turn into cats and, with animal guards, sneak into churches and crap on the floor. I can't help but see this as another instance of the film discussing a sort of subversive tactic taken against oppression.

Also it has these hilarious costumes of the people dressed up as cats.... like, they could've just used real cats. But no, they made like, four or five of these costumes.

directed by Benjamin Christensen

TW: for discussion of oppression, historical torture (inquisitions mostly), religious abuse, and coerced psychiatry.

How do we take a movie like Häxan? In some ways I feel like watching this is akin to watching DW Griffith's Birth of a Nation. On one hand, it's a piece of filmic history, on the other it's a reiteration of what were (and are) systemic injustices and violences done upon various marginalized bodies (women in the former and black people in the latter).

I'll grant that Häxan is probably not as purposefully inflammatory as Griffith's film. It takes its subject, the history of witchcraft and the treatment of women accused as witches throughout history, as a symptom of a bygone superstitious belief system supplanted by scientific insight and more modern medicine.... but that's.. well we'll get there.

The film begins with a recounting of various myths from throughout history, landing on how the conception of medieval Christianity conceived of the world as existing in spheres, at the top of which sat the Christian God and at the bottom of which was found Hell.

From here, we're informed of the belief that throughout history certain women were perceived as being particularly susceptible to the influence of the devil. It's interesting that the movie's portrayal of this history is very much of a double consciousness about this. On the one hand, these women are to be pitied and helped (oh the help...), but this is most often when they are in the company of men. When these women congregate together, they are feared. There are some really stunning shots during this part of the movie as the film shows the witches in flight across various nighttime foreground structures.

From this somewhat empowering view of the witch as an object of fear, the movie then moves us forward to a period where religious persecution holds sway. In this segment of the movie, we see that the movie does at least know that the treatment of women at this time was vile. Women are pressured into confessions under threat to their loved ones, and are routinely killed after enduring horrible torture at the hands of these monks and inquisitors. It's really at times some pretty brutal stuff, and there's a real sense of the injustice of the time.

After wrapping this up, the film begins its conclusion that's a bit... well, it's cause for reflection. The film was made in 1922, and I imagine was one of the very early documentary style films. The film has a very "look how far we've come" attitude about the attitudes toward women. Saying that what used to be called witchcraft.... is now properly known as hysteria....

The funny thing is, I think the film's a bit of a mirror. So many people still berate feminists with this idea that because women are now able to do X action (vote, work, have birth control), that we've somehow totally overcome sexist ideology. In this way, Häxan seems less like an opportunity to shake our heads at the ignorance and misogyny of these people in 1922, and more as an invitation to look at how this same sort of pattern of thought is ongoing and insidious, and that changes to ideology (such as the introduction of intersectionality to feminism) are needed as a fine-tuning instrument, lest we claim some action or movement as a panacea for oppression (as psychiatry is posited in this film).

Given this, I also think that the sympathetic portrayal of the witch is interesting. I have several female-identifying friends who associate strongly with various forms of witchcraft, paganism, and Wicca. I think that in some ways these are oftentimes counter-narratives that go against the patriarchal narratives instituted by Western Abrahamic religious hegemony. It's a subversive tactic, and the shot that I'm reminded of the most comes from the end of the witch segment of the movie. In it, it's explained that it was believed that witches would turn into cats and, with animal guards, sneak into churches and crap on the floor. I can't help but see this as another instance of the film discussing a sort of subversive tactic taken against oppression.

Also it has these hilarious costumes of the people dressed up as cats.... like, they could've just used real cats. But no, they made like, four or five of these costumes.

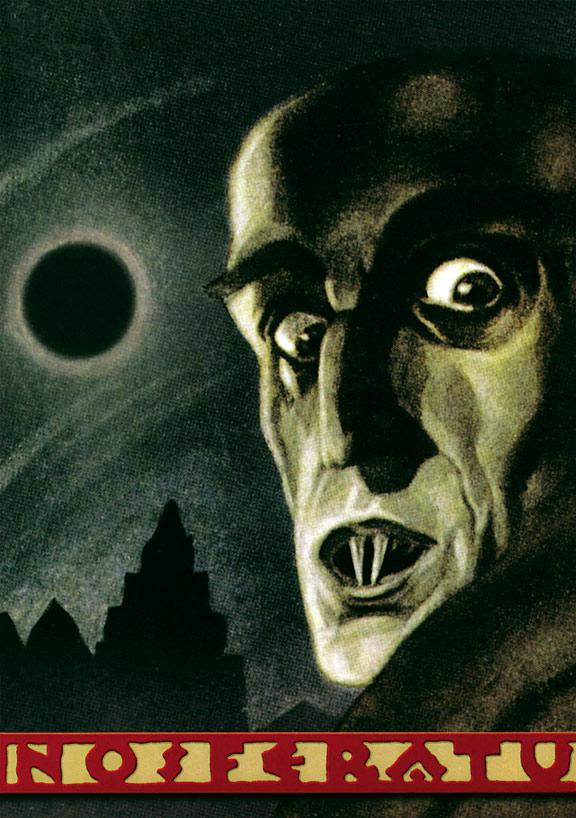

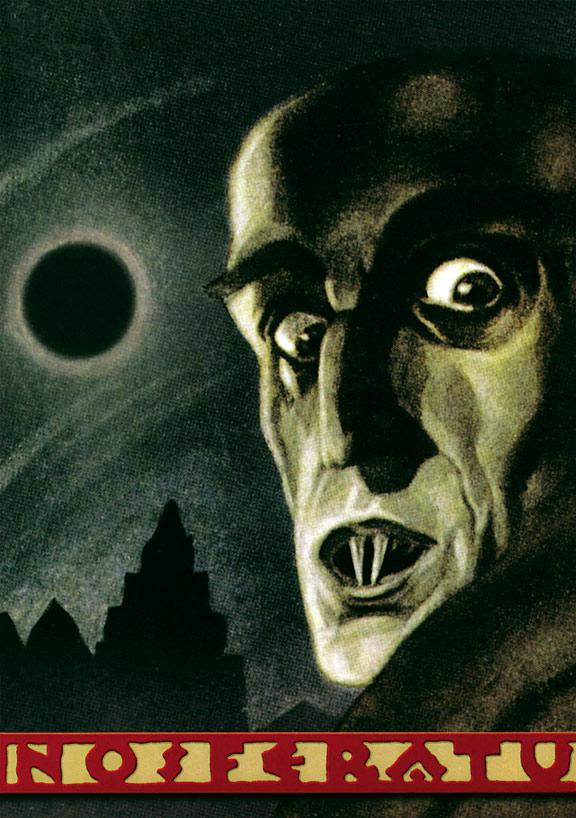

Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens

Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens

directed by F.W. Murnau

Okay so it's not a criterion film, but it's part of another film list I'm working through, the 366 weird movies list found on 366weirdmovies.com. Also I wanted to watch a movie for Halloween that I hadn't seen yet, so I figured this would be a good opportunity for it.

So, going in, I knew that Nosferatu featured a rather marked variation from the standard Holywood vampire. Even Lugosi played a more attractive vampire than Schreck's Orlok, who I always thought looked kind of silly and uncomfortable in his costume. Other than that, though, I only knew of the films legal troubles with the Stoker estate.

Overall, I think Nosferatu is an interesting yarn that really dwells in its atmosphere very well. From the moment the film introduces Hutter's (this film's Jonathan Harker) boss Knock, there's this off-kilter feeling. I remember back in undergrad I watched The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari for a Horror-film class that I was in, and I was struck by the highly expressionistic set design of the film. Although Nosferatu came out two years after Caligari, it has a markedly different visual language to it. This isn't a bad thing, although... well I'll get to this later.

The shots that this country gives of the European countryside are just absolutely gorgeous! Unfortunately I couldn't really find any to post here, but there are many shots of mountains, rivers, and fields that just give this stunning view of what're supposed to be the Carpathians I believe.

Once Hutter meets Orlok, I will say that the film differs in a number of ways from Stoker's novel. Where Dracula was charming and polite, Orlok almost immediately tries to drink Hutter's blood. Also, notably, the brides are absent from this film. This isn't really a problem, but it does make Hutter's need to "escape" the castle once Orlok has left a little less clear.

The film differs drastically from the book at the end. The character of Ellen, Hutter's wife, who is sort of a combination of both Lucy Westenra and Mina Harker, seems to know that she needs to sacrifice herself so that Orlok will die in the sunlight. I did initially wonder if there wasn't any other way, but I kind of knew her death was coming toward about the midway point in the movie. I will say, I did notice as the movie went on though that Ellen is really the protagonist of the film. Hutter sets up the initial interaction between Orlok that prompts him to come to Germany, but from there all of the conflict revolves around Ellen and her figuring out how to set up Orlok's death. I'm somewhat uncomfortable with the whole "women dying in horror movies" stock thing, but I guess I'm a little bit more okay with it when it's more of a sacrifice to kill the film's monster. What're other folks thoughts on this?

A few other observations, most of which are minor nitpicky things

-There's a point in the film where an innkeep warns Hutter of a werewolf that prowls at night, and we get a shot of this werewolf and... it's so clearly a Striped Hyena. It's also adorable.

-Orlok at one point carries his coffin through the German town he's bought a house in and it's hilarious to watch. He's sort of awkwardly holding it under his arms and walking like he's trying to sneak around with it. Also, it's very obviously daylight in these shots, and I think we're just supposed to pretend it isn't. Maybe this is one of those things that would've been less apparent on older film.

Okay so it's not a criterion film, but it's part of another film list I'm working through, the 366 weird movies list found on 366weirdmovies.com. Also I wanted to watch a movie for Halloween that I hadn't seen yet, so I figured this would be a good opportunity for it.

So, going in, I knew that Nosferatu featured a rather marked variation from the standard Holywood vampire. Even Lugosi played a more attractive vampire than Schreck's Orlok, who I always thought looked kind of silly and uncomfortable in his costume. Other than that, though, I only knew of the films legal troubles with the Stoker estate.

Overall, I think Nosferatu is an interesting yarn that really dwells in its atmosphere very well. From the moment the film introduces Hutter's (this film's Jonathan Harker) boss Knock, there's this off-kilter feeling. I remember back in undergrad I watched The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari for a Horror-film class that I was in, and I was struck by the highly expressionistic set design of the film. Although Nosferatu came out two years after Caligari, it has a markedly different visual language to it. This isn't a bad thing, although... well I'll get to this later.

The shots that this country gives of the European countryside are just absolutely gorgeous! Unfortunately I couldn't really find any to post here, but there are many shots of mountains, rivers, and fields that just give this stunning view of what're supposed to be the Carpathians I believe.

Once Hutter meets Orlok, I will say that the film differs in a number of ways from Stoker's novel. Where Dracula was charming and polite, Orlok almost immediately tries to drink Hutter's blood. Also, notably, the brides are absent from this film. This isn't really a problem, but it does make Hutter's need to "escape" the castle once Orlok has left a little less clear.

The film differs drastically from the book at the end. The character of Ellen, Hutter's wife, who is sort of a combination of both Lucy Westenra and Mina Harker, seems to know that she needs to sacrifice herself so that Orlok will die in the sunlight. I did initially wonder if there wasn't any other way, but I kind of knew her death was coming toward about the midway point in the movie. I will say, I did notice as the movie went on though that Ellen is really the protagonist of the film. Hutter sets up the initial interaction between Orlok that prompts him to come to Germany, but from there all of the conflict revolves around Ellen and her figuring out how to set up Orlok's death. I'm somewhat uncomfortable with the whole "women dying in horror movies" stock thing, but I guess I'm a little bit more okay with it when it's more of a sacrifice to kill the film's monster. What're other folks thoughts on this?

A few other observations, most of which are minor nitpicky things

-There's a point in the film where an innkeep warns Hutter of a werewolf that prowls at night, and we get a shot of this werewolf and... it's so clearly a Striped Hyena. It's also adorable.

-Orlok at one point carries his coffin through the German town he's bought a house in and it's hilarious to watch. He's sort of awkwardly holding it under his arms and walking like he's trying to sneak around with it. Also, it's very obviously daylight in these shots, and I think we're just supposed to pretend it isn't. Maybe this is one of those things that would've been less apparent on older film.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)